Gaming culture doesn’t cross over into luxury. That’s been the prevailing wisdom for decades, reinforced by a consumer electronics industry that treats gaming hardware as a performance category and luxury goods as a separate conversation entirely. The two worlds coexist on the same retail floors but rarely in the same sentence. Luxury brands court minimalism and restraint. Gaming brands chase RGB lighting and aggressive angles. One speaks to taste, the other to specs. But there’s a specific moment happening right now that suggests the wall between those worlds isn’t just cracking, it’s being deliberately dismantled from the gaming side.

Death Stranding 2: On The Beach is one of the most anticipated game releases of 2026, carrying search interest that’s spiked over 230% in the past year alone. Hideo Kojima’s name is trending globally, not because of controversy or nostalgia, but because his studio is releasing a sequel that positions connection, isolation, and environmental collapse as interactive entertainment. That cultural momentum has created something unusual: a game director whose relevance extends beyond the gaming press and into design, fashion, and technology conversations. When Kojima Productions announced a hardware collaboration with ASUS Republic of Gamers, it didn’t register as a typical special edition. It registered as a design event.

The filmmaker who chose a different screen

To understand why that distinction matters, you have to understand the person behind it. Kojima isn’t a brand ambassador lending a name to a product. He’s a creative director whose entire career has been built on the belief that interactive media can carry the emotional weight of cinema. That conviction has shaped everything from his earliest games to the laptop sitting on our desk right now.

Hideo Kojima was born in Tokyo in 1963, during Japan’s postwar economic boom. His father died when Kojima was young, an experience he’s spoken about openly as the root of his obsession with loss, connection, and the spaces between people. Before he ever touched a game console, he wanted to make films. That cinematic ambition never left. It shaped his approach to game design, his insistence on long cutscenes, his casting of Hollywood actors, his treatment of controllers as cameras rather than weapons. He joined Konami in 1986, entering an industry that was still mechanically driven and light on narrative. What he brought to it was a filmmaker’s impatience with the limitations of the medium.

In 1987, Kojima created Metal Gear, a game that introduced stealth as a core mechanic when the rest of the industry rewarded direct combat. Instead of running toward enemies, players avoided them. That single design choice redefined a genre and launched a franchise that would span decades. Metal Gear Solid expanded the concept into something closer to interactive cinema, blending political commentary, fourth-wall-breaking moments, and narratives so layered they bordered on impenetrable. Critics called the approach self-indulgent, but the audience it built was fiercely loyal and unusually literate in design language.

What separated Kojima from other celebrated game directors wasn’t just ambition. It was consistency of vision across wildly different scales. He treated a codec conversation with the same directorial attention as a boss fight. Over twenty years at Konami, he built something rare in gaming: a personal brand that existed independently of the company that employed him.

What happens when a company erases your name

That independence became a problem. In 2015, Kojima’s relationship with Konami publicly collapsed during the development of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. His name was removed from the game’s marketing materials. Silent Hills, a highly anticipated horror collaboration with filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, was cancelled. Reports from inside Konami described budget disputes, creative friction, and a corporate culture increasingly hostile to the kind of expensive, auteur-driven projects Kojima insisted on making. The split was public, bitter, and closely followed by an industry that understood the stakes. When one of gaming’s most recognizable creators walks away from the franchise that defined both his career and his employer’s identity, the fallout isn’t just professional. It’s cultural.

What followed was a period of industry speculation about whether Kojima could survive outside the Konami ecosystem. The franchise, the infrastructure, the global distribution network: all of it stayed behind. Kojima walked away with his reputation and a list of collaborators willing to follow him.

A studio mascot that isn’t just a mascot

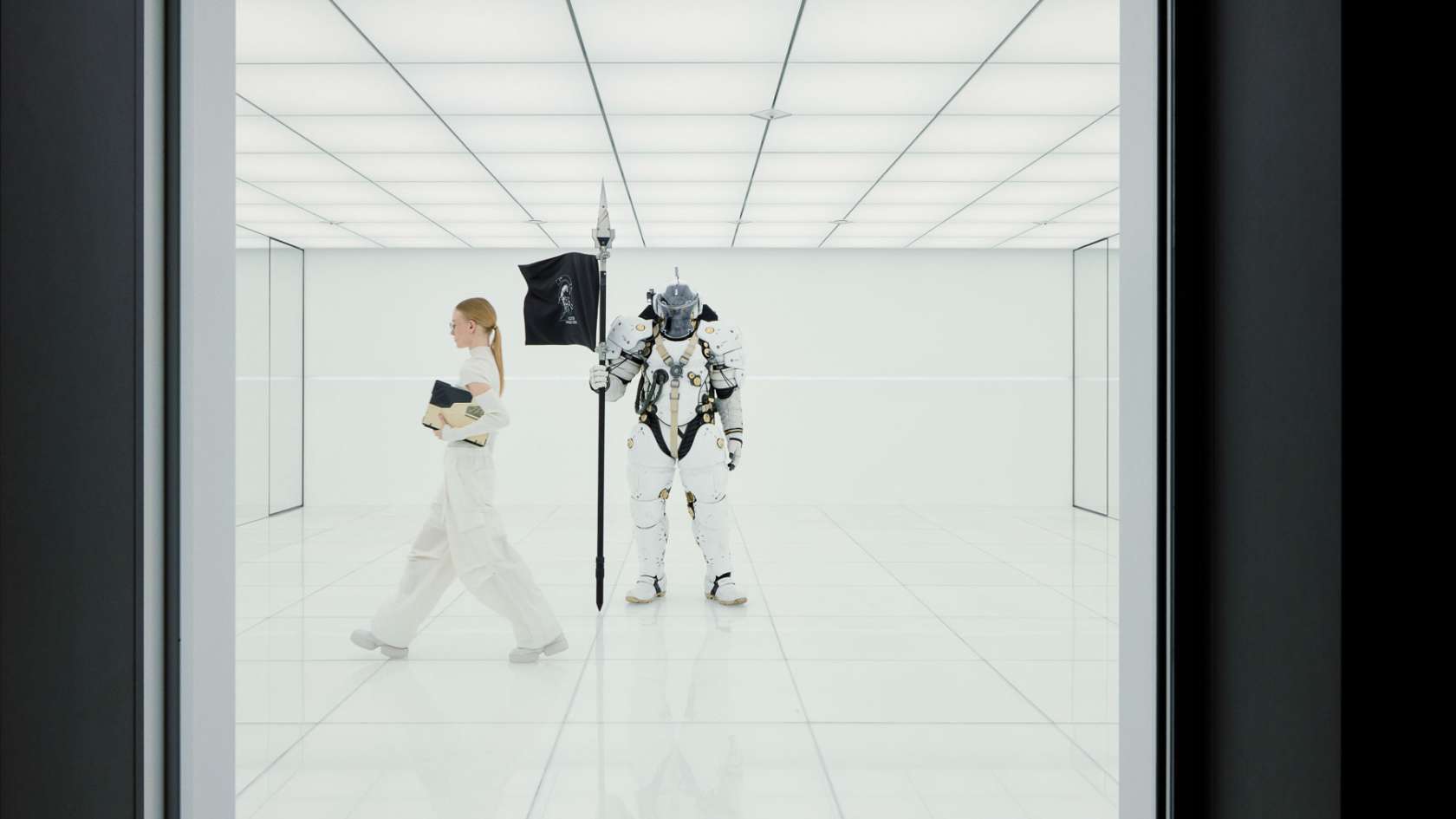

He founded Kojima Productions as an independent studio in December 2015, with Sony providing backing for the first major project. The studio adopted Ludens as its mascot: an astronaut figure representing exploration and the spirit of pushing into unknown creative territory. It was a deliberate signal. Kojima Productions wasn’t going to make safe sequels or licensed content.

Death Stranding, released in 2019, divided players more sharply than anything Kojima had made before. Some dismissed it as a walking simulator wrapped in pretentious cutscenes. Others recognized it as a meditation on human connection in a world that had literally come apart. Commercially, it performed well enough to greenlight a sequel. More importantly, it proved that Kojima could build an original IP from scratch, outside the safety net of Metal Gear, and find an audience willing to meet him on his own terms.

When a laptop becomes a prop in someone else’s universe

Here’s what most coverage of Kojima misses. His influence stopped being confined to game design years ago. The studio’s visual identity, developed in collaboration with artist Yoji Shinkawa, functions more like a fashion house’s creative direction than a game developer’s art department. Ludens isn’t just a logo. It’s a design language that extends to physical objects, apparel, and now, computing hardware. When a game studio starts operating like a design label, the products it touches stop being merchandise and start becoming cultural artifacts.

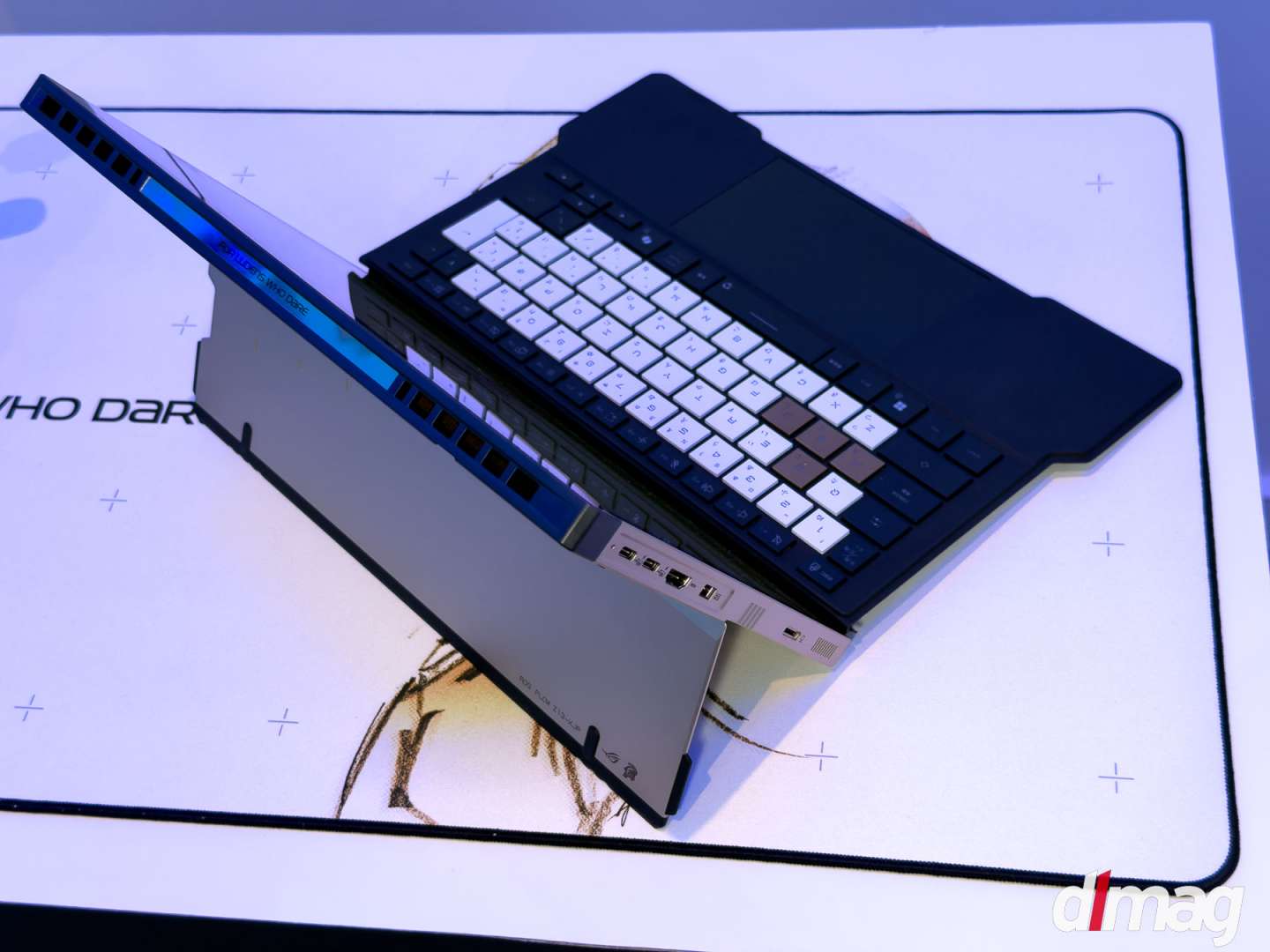

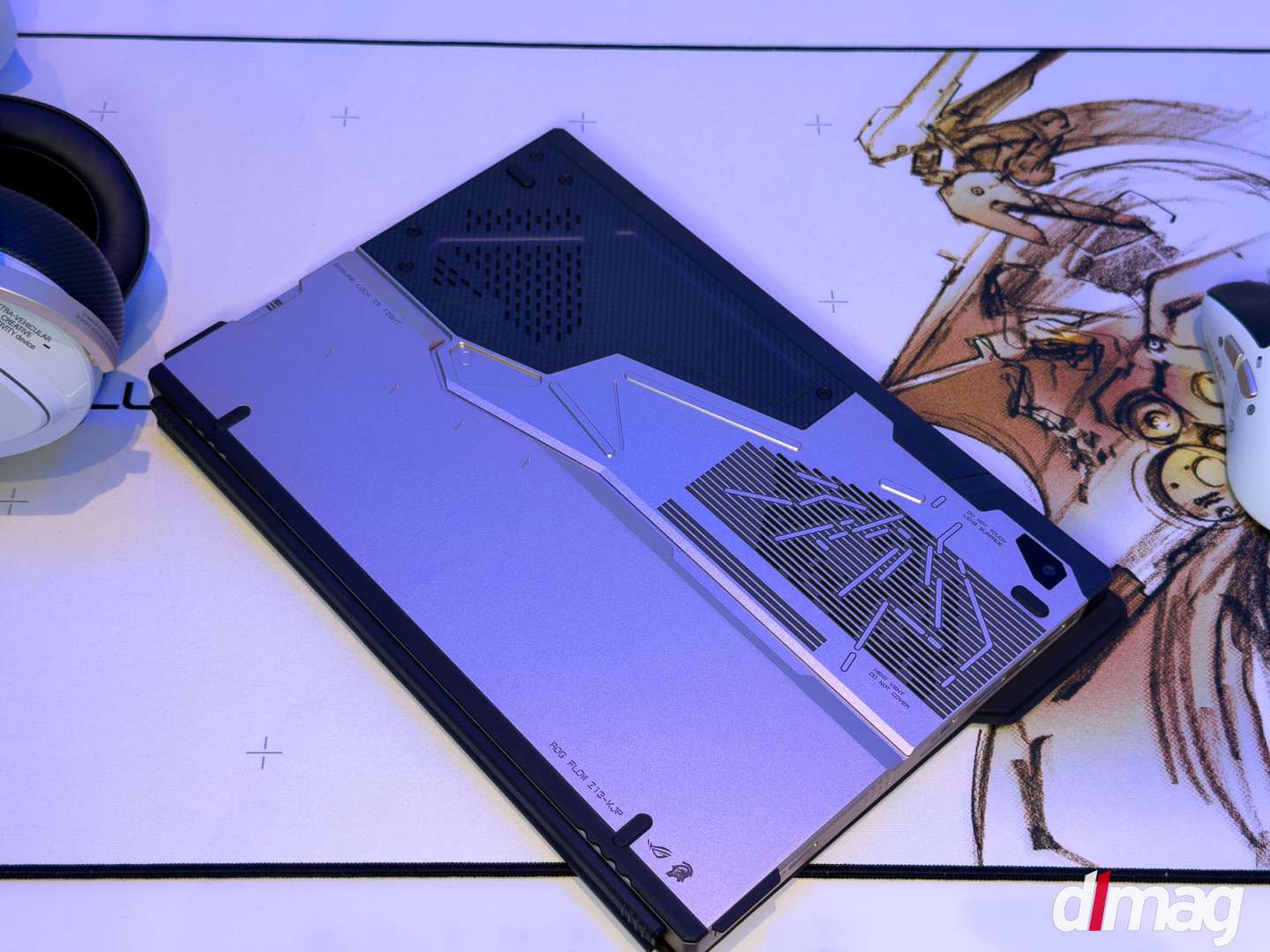

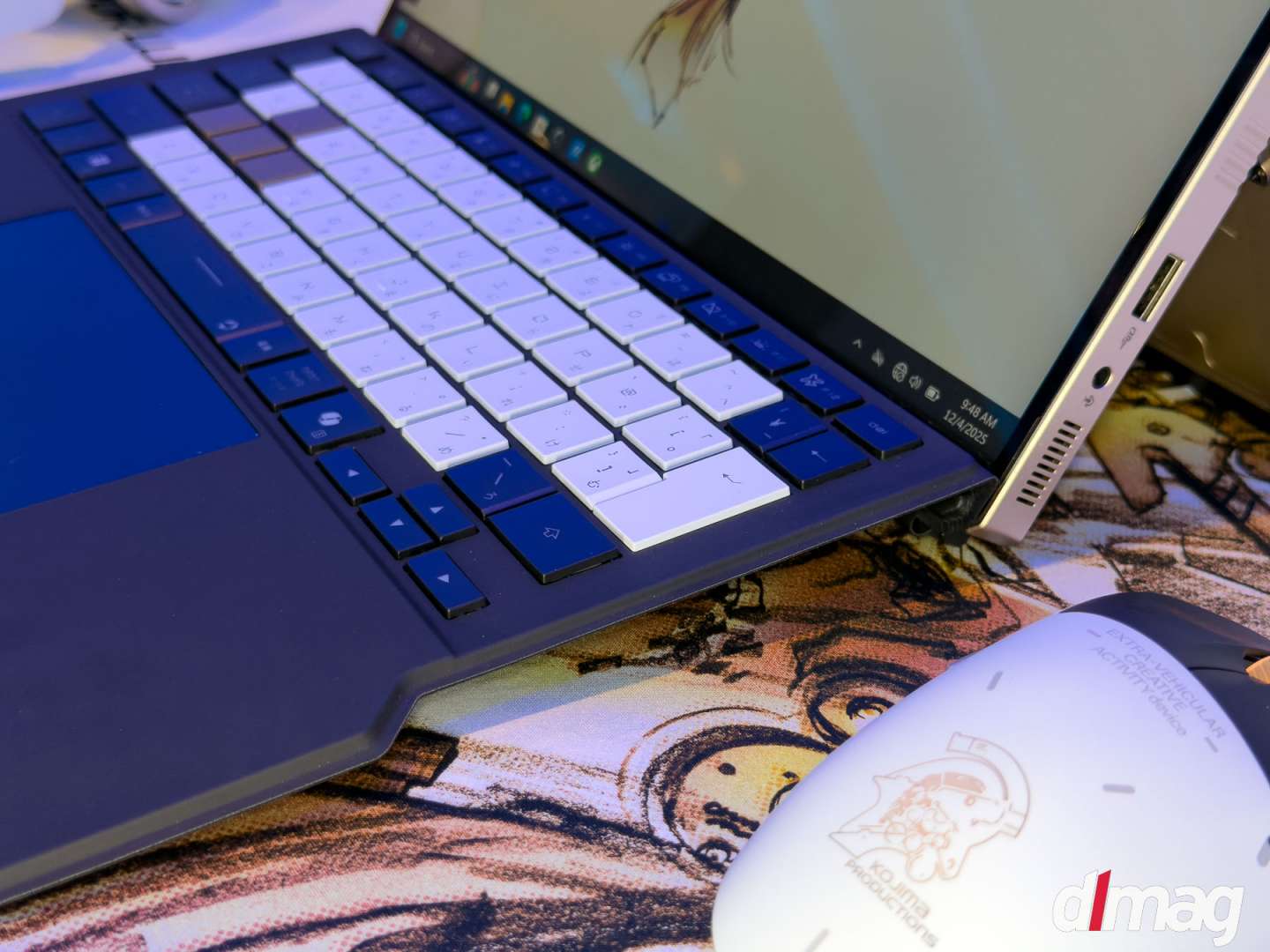

The ASUS ROG Flow Z13 Kojima Productions Edition is the most tangible expression of that shift. It isn’t a gaming laptop with a logo slapped on the lid. The entire device was designed in collaboration with Kojima Productions and Yoji Shinkawa, whose illustration work defined the visual language of Metal Gear Solid and Death Stranding. The chassis is CNC-milled aluminum paired with carbon fiber, materials chosen for texture and weight as much as durability. Shinkawa’s artwork is integrated into the physical design rather than printed on top of it. The packaging, the accessories, even the peripheral ecosystem (a matching ROG Delta II KJP headset and branded peripherals) are treated as components of a single creative vision. This is hardware as world-building, the same philosophy Kojima applies to game environments translated into the object you hold in your hands.

Pick up the Z13 KJP and the first thing you notice isn’t the screen or the specs. It’s the weight distribution. The tablet form factor, detached from its keyboard, feels denser than you’d expect from a 13-inch device, the kind of heft that signals real materials rather than plastic shells. The CNC-milled aluminum surface has a distinct tactile quality under your fingertips, a precision you can feel even before you power it on. Shinkawa’s design elements are integrated into the chassis, not applied to it. The Ludens emblem on the rear panel catches light differently depending on the angle, a detail that photographs can’t fully capture.

Under that exterior sits an AMD Ryzen AI Max+ 395 processor paired with Radeon 8060S graphics and 128GB of unified memory, a configuration that positions the Z13 KJP as a workstation-class machine compressed into a tablet form factor. For context, that memory ceiling exceeds most 15-inch gaming laptops and matches configurations typically reserved for professional content creation rigs costing significantly more. The Z13 KJP ships with Death Stranding 2: On The Beach for PC at launch, which feels less like a pack-in bonus and more like a statement of intent: this machine was built to run the game its collaborator created.

Shinkawa’s contribution is worth examining on its own terms. His illustration style, characterized by fluid ink work and a tension between mechanical precision and organic movement, has defined the aesthetic of Kojima Productions since the original Metal Gear Solid. Translating that style from concept art to industrial hardware required a different kind of collaboration than simply licensing artwork. The Z13 KJP’s design language reflects Shinkawa’s visual philosophy without reducing it to decoration, treating the laptop’s surfaces as canvases that carry narrative weight.

Gaming’s quiet move into the luxury conversation

Pre-orders for the Z13 KJP open February 24, and the timing isn’t accidental. Death Stranding 2’s release window creates a convergence point where Kojima’s cultural visibility, gaming hardware demand, and collector interest all peak simultaneously. This is the pattern luxury fashion has used for decades: tie a limited product to a cultural moment and let scarcity do the rest. But there’s a meaningful difference here. Fashion collaborations typically borrow cultural credibility from an outside partner. The Z13 KJP generates its own, because Kojima Productions isn’t licensing a name to ASUS. The studio is extending its creative universe into a new medium.

Gaming culture has been quietly evolving toward this moment for years. The audience that grew up with Metal Gear Solid is now in its thirties and forties, with disposable income and a design vocabulary shaped by decades of interactive media. They don’t just buy hardware for performance. They buy it for identity, for the same reasons someone chooses a specific watch or a particular pair of sneakers. The Z13 KJP is positioned squarely at that intersection: a performance machine that also functions as a cultural signifier.

Who this is actually for

The Z13 KJP makes the most sense in the hands of someone who already treats technology as a design category. Collectors who display limited edition sneakers next to first-edition art books will immediately understand what Kojima Productions and Shinkawa built here. The carbon fiber, the CNC-milled aluminum, the integrated artwork, these are material decisions that reward the kind of person who notices stitching on a leather good or the weight of a well-made pen. If you’ve ever chosen an object because of who made it rather than what it does, this laptop was designed with your instincts in mind.

There’s a second audience that matters just as much: people who grew up inside Kojima’s creative universe and now have the means to own a physical piece of it. Death Stranding and Metal Gear Solid shaped an entire generation’s visual vocabulary. For that audience, the Ludens emblem on the rear panel isn’t branding. It’s shorthand for a creative philosophy they’ve followed across decades, studios, and platforms. The Z13 KJP gives that relationship a tangible form, something you can hold, use daily, and display with the same intention as a gallery piece.

Kojima Productions is betting that a small, culturally literate audience will value this machine differently than the mainstream market values any laptop. Based on what we’ve seen so far, that bet looks well placed.

The bottom line

We have the Z13 KJP on our desk right now, and we’re spending time with it before sharing a full review. First impressions suggest this is a device that rewards close attention, both in how it performs and in the details Kojima Productions embedded throughout the design. More on that soon.

Hideo Kojima spent four decades proving that games could carry the weight of cinema. Then he proved a studio could survive losing everything except its creative identity. Now he’s proving that a game designer’s vision can translate into physical objects that feel like artifacts rather than accessories. The Z13 KJP is the latest piece of evidence for that argument. Whether it changes how the industry thinks about hardware collaborations depends on whether other studios have the cultural authority to attempt something similar, and right now, the list of candidates is very short.