Sake is still somewhat shrouded in mystery for many consumers in the west, but you should really give it a try and discover what Japan’s national drink is all about. Some say that sake is an acquired taste. If this is true, then the world is made of those have acquired the taste and those who have yet to.

But beware because once you are bitten by the Japanese sake bug, you’ll forget that your life never had sake in it as a new world of drinking pleasure opens up before you. But before you dive into the traditional rice wine of Japan headfirst, it helps to understand how it is made and the different grades available in order to fully appreciate this wonderful drink.

Time to go over the basics

The word ‘Sake’ actually just means alcohol in Japan, whereas the rice-based drink that we know as sake is called ‘nihonshu’ by the Japanese and is made from rice. The traditional drink has been made in Japan for over 1,000 years, but at more of an agrarian level. Which is also one of the reasons sake is sometimes drunk warm it mask any impurities. However, the premium form of sake, such as ginjo, has only been in production for the last fifty or so years.

There are approximately seventy rice varieties that are used for the production of sake. However, the three main varieties are: yamadanishiki, gyohakumangoku, and miyamanishiki. These three make up almost three-quarters of the total rice-cropping area.

In terms of percent alcohol, sake generally comes in around 15 to 16% ABV, but as always, there are exceptions to every rule out there. The other really nice thing about sake is that it has one fifth the acidity of wine – make it an excellent choice for those with stomach sensitivities. Okay, sake may not have the crisp and refreshing acid taste of wine, but it does have a lot of texture and subtlety of flavor and much diversity of style.

Polishing and Fermentation

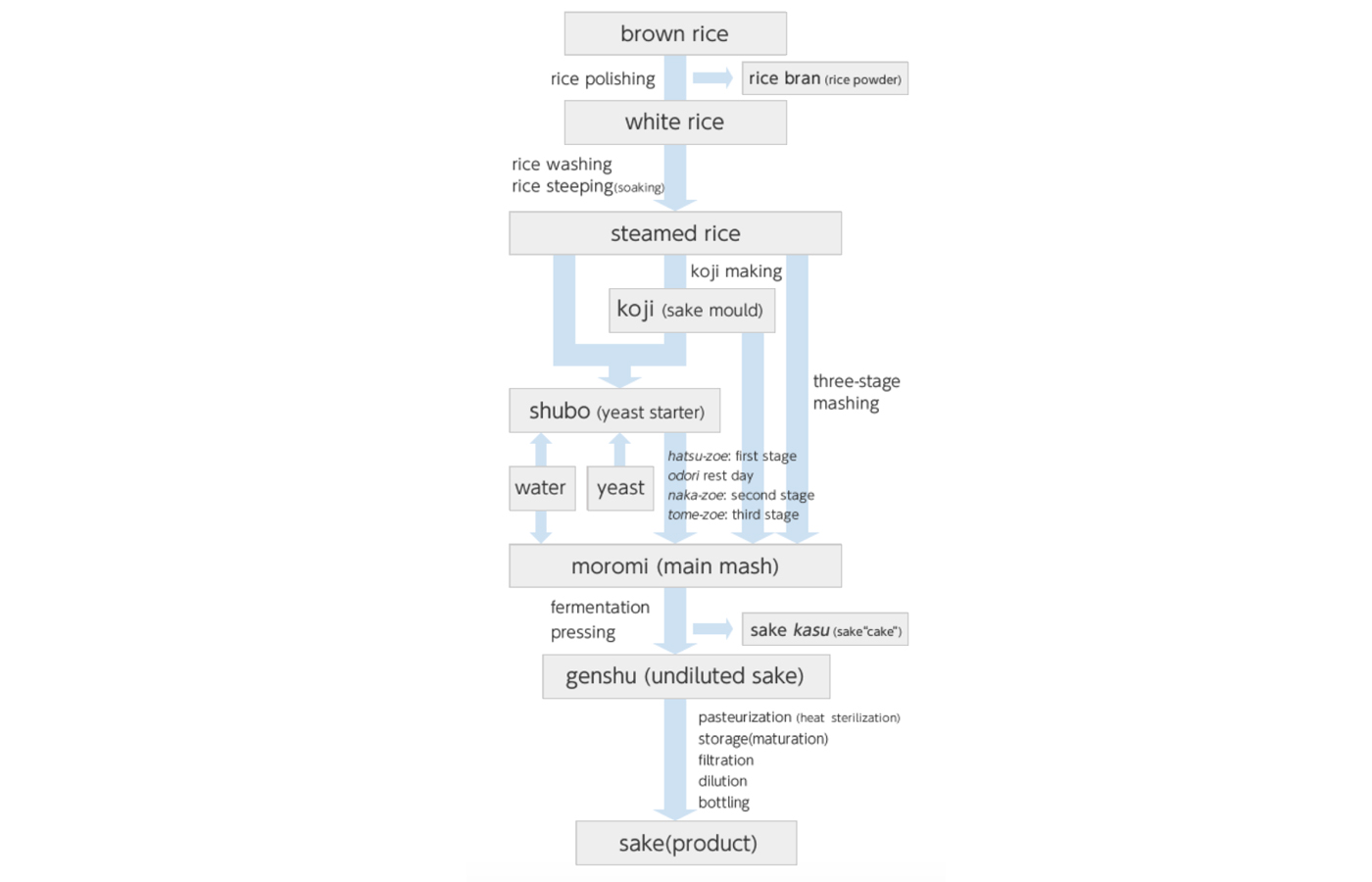

Determining polishing will indicate the grade. Quality grades are figured out according to the polishing ratio. What does that mean exactly? Well, how much of the grain of rice is milled away before the starchy core is ready to be converted by the koji mold to fermentable sugar. Sake grades and prices are a rule of thumb guide to quality but, it is often in your best interest to sample a lower grade from a top brewery (but not always).

Okay, now it is said that most of the contribution to the style and flavor of the rice wine comes from the intentions, goals, and techniques of the brew master, otherwise known as the Tōji. At the brewery, the rice is washed, steamed, and then, cooled down before a fifth of it is spread on a wooden table where the koji mold spores are added in order to break down the starch into fermentable sugar.

A handful of Sake styles you should know

Generally speaking, the first two listed below, daiginjo and ginjo, have fruity and floral frangrances, and are popular drinks served chilled. Whereas the other two on the list, honjozo and Junmai, can cover a broad range of value and versatility, especially when it is consumed with food, and therefore, is served at a wider range of temperatures.

- Daiginjo is a super-premium and quite fragrant sake with a minimum of 50% polishing ratio. A small amount of distilled alcohol is added to enrich the flavor and enhance the aroma. This sake is best served chilled.

- Ginjo is a premium and fragrant sake with a minimum of 40% polishing ration and quite similar to daiginjo.

- Honjozo is a light and mildly fragrant premium sake polished with a minimum of 70% ratio and has a small amount of distilled alcohol put in for aroma and flavor.

- Junmai is a sake made with nothing more than rice, water, yeast, and koji and has no minimum polishing ratio. Also, there is no addition of extra alcohol to this recipe.